Hugh Edwards

Nick Hsieh

Eric Phe

Pat Palalikit

Darin Truong

The arctic tundra biome occurs at northern (high) latitudes and mountaintops, in areas where precipitation is sparse, temperatures are low, and sunlight is diffused. In these areas, the ground is frozen (permafrost) for about 7 months each year with very low precipitation of between 10 cm and 25 cm per year. Due to the extreme climate in these areas, there is relatively low biodiversity with 1,700 plant species and 48 species on land mammal. However, it is home to a large number of migratory animals for parts of the year. As for the vegetation in this ecosystem, they are mostly prostrate perennials due to the short growing season and high winds. On a global scale, this type of ecosystem occurs in places like Canada, Alaska, Greenland, Scandinavia, and Siberia; this post will focus on the Alaskan tundra.

Tundra Areas Around the World

History of the Alaskan Tundra

Map of Tundra Biomes in Alaska

The Alaskan tundra in its historical, non-human-impacted state is a treeless, somewhat barren ecosystem. Due to both very cold temperatures and low precipitation, the arctic tundra in Alaska is not capable of supporting an abundance of primary production; therefore, vegetation presents itself in the form of short perennials (sedges, shrubs, and the like) that only put out a small spurt of growth each year. The relatively little growth in this ecosystem is also due to a third factor: lack of light. Because Alaska is situated at a northern latitude, its tundra experiences long winters with short days and short summers with long days. Even during these summers, however, sunlight hits at a very low angle, spreading across a wider expanse; in essence, the light is diffused, making it more difficult for plants to carry out photosynthesis.

A defining characteristic of the tundra is permafrost, the permanently frozen layer of soil and decaying organic matter that make up the composition of the land. Because permafrost also holds water, it yields moisture during the summer that allows for plant and animal growth. It is what enables the existence of wetlands and small lakes in an ecosystem that otherwise receives very little precipitation (10-25 cm, mostly in the form of winter snow). Furthermore, permafrost plays an important role in maintaining the overall biosphere, serving as a major carbon sink.

Geographically, arctic and subarctic tundra occurs in northern and western Alaska. While central Alaska is characterized by boreal forests, the land transitions into a more barren tundra closer to the Arctic Circle and to the western coast and Aleutian Islands. Alaskan tundra encompasses an area of 103,814 square kilometers.

Human Impact

Global warming in the Arctic is the main threat to this ecosystem since humans don’t visit or live much in the Arctic tundra. As the temperature rises, the permafrost starts to melt which contains a lot of dead plant material. When this plant material decays, it releases CO2 and methane into the atmosphere, contributing to global warming and allowing for invading plants to sprout. In addition, the thawing of permafrost equates to erosion which becomes an issue because now, the soil is not being held in place. As the ecosystem changes where the seas and weather gets warmer, certain species will no longer be able to live there. For example since the ice is melting earlier in the year, polar bears don’t have enough time to gather their food, leading to starvation. The sea level will also inevitably rise as ice and glaciers melt; surrounding areas will flood, killing many plant species. Air pollution caused by greenhouse gases also contaminates lichens and mosses, significant food sources for many animals. The lichens are extremely vulnerable to pollution due to their lack of roots and their dependency on air nutrients. Industrial air pollutants are being carried to the Arctic on air currents from populated areas. Air pollution has also led to the famous “arctic haze” phenomenon, which contributes to acid rain in the ecosystem, further melting the permafrost. In conjunction with the melted plant material, the landscape has become drier, causing wildfires throughout Alaska.

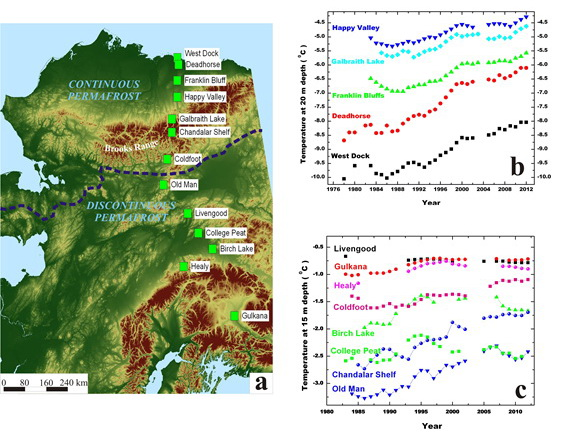

Temperature Changes in Permafrost

Graph of the World’s Carbon Sinks

Permafrost Loss in Alaska

http://www.livescience.com/49184-permafrost-disappears-from-alaska.html

Another impact occurs when humans explore oil, gas, and minerals in the Arctic. The construction of pipelines and roads for these resources can cause physical disturbances and habitat fragmentation. Also, many plants and animals have been killed or forced to flee the area after having their ecosystem contaminated by harmful gases and materials during oil drilling. Oil spills also kill wildlife and significantly damage the ecosystem.

Oil and Gas Exploration in Alaska

Oil Rig in Alaska

A few things that can be done to improve this ecosystem is to set restrictions on major contributing sources. For the mobile portion of the issue, promoting more eco-friendly vehicles is the way to go. As we promote, consumers are more likely to accept. In regards to the factory portion, stricter tests must be set in place to prevent the contamination of air. Without these tests, we are furthering ourselves down a road with a near end. Implementing these changes will help slow further human-induced damage.

The fate of the vast carbon stock held in permafrost has become a major concern to global-change scientists because its release to the atmosphere could exacerbate CO2–related climate change. In addition, global warming impacts the northern hemisphere much more than anywhere else on the planet. Any global warming created anywhere in the world will ultimately impact the tundra in the long term. The tundra is particularly sensitive to global warming, as it depends on colder temperatures to maintain its specific blend of vegetation. After the permafrost melts, the unfrozen land is likely to be taken over by boreal forest as the landscape continues to warm. Solutions that the world can take on to preserve the tundra is to mitigate global warming and ocean acidification, which in turn helps to prevent permafrost loss. Wind, nuclear, and solar power as alternative sources of energy, for example, could be used in lieu of fossil fuels.

Sources of Greenhouse Gas Emissions

http://www3.epa.gov/climatechange/ghgemissions/sources/electricity.html

The fate of the vast carbon stock held in permafrost has become a major concern to global-change scientists because its release to the atmosphere could exacerbate CO2–related climate change. In addition, global warming impacts the northern hemisphere much more than anywhere else on the planet. Any global warming created anywhere in the world will ultimately impact the tundra in the long term. The tundra is particularly sensitive to global warming, as it depends on colder temperatures to maintain its specific blend of vegetation. After the permafrost melts, the unfrozen land is likely to be taken over by boreal forest as the landscape continues to warm. Solutions that the world can take on to preserve the tundra is to mitigate global warming and ocean acidification, which in turn helps to prevent permafrost loss. Wind, nuclear, and solar power as alternative sources of energy, for example, could be used in lieu of fossil fuels.

U.S. Greenhouse Gas Inventory Report: 1990-2013

http://www3.epa.gov/climatechange/ghgemissions/usinventoryreport.html

There are also sustainable practices for resource management we should adopt in Alaska to protect the tundra. For instance, further oil drilling preventive measures will preserve this delicate landscape and its habitat in the future. Oil drilling decimates the landscape; lots of Alaskan oil reserves are located directly below tundra. Also, an oil spill of any kind would significantly damage the surrounding ecosystems. We can expand wilderness protection areas in Alaska to prevent excessive harvesting, hunting, and drilling in the tundra. A reduction of tourism in select tundra sites would also reduce human degradation of the landscape by mitigating the number of new roads, buildings, and trails constructed on tundra lands.

Protection of the Alaskan Tundra

Unlike many other ecosystems, there are a large number of protected areas for the Alaskan tundra, including:

Unlike many other ecosystems, there are a large number of protected areas for the Alaskan tundra, including:

- Lake Clark National Park and Preserve (southern Alaska)

- Denali National Park (South Central Alaska)

- Tetlin National Wildlife Refuge (Southeastern Alaska)

- Wrangell-St. Elias Park and Preserve

- Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR)

Out of these many protected areas, the most significant protected area for this ecosystem is the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR). The ANWR is the largest national wildlife refuge in the United States, spanning over 19.6 million acres, and is one of the most pristine and intact, naturally functioning arctic/subarctic ecosystems in the world.

Initially the ANWR was established in 1960 as the Arctic National Wildlife Range “for the purpose of preserving unique wildlife, wilderness, and recreational values”. In 1980, the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act (ANILCA) re-designated the Range as part of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. The management of the entire Refuge is guided by 4 key philosophies: “to conserve animals and plants in their natural diversity, ensure a place for hunting and gathering activities, protect water quality and quantity, and fulfill international wildlife treaty obligations”.

The ANWR is not entirely designated as a wilderness area, the highest possible level of conservation protection in which the area is permanently left in its natural condition, but is divided into three primary areas: the Mollie Beattie Wilderness (designated as wilderness area, 8 million acres), Coastal Plain (1002 Area - Petroleum Assessment Area, 1.5 million acres), and minimal management area (10.5 million acres).

The ANWR is home to 37 species of land mammals, eight marine mammals, 42 fish species, such as polar and brown bears, caribou, Dall sheep, wolves and muskox, as well as more than 200 migratory bird species. Another unique feature of the ANWR is that this area encompasses an unbroken continuum of arctic and subarctic ecosystems. Furthermore, it is the traditional homeland of a number of native tribes such as the Inupiaq Eskimos of the Arctic coast.

| http://wikidoo.wikidot.com/anwr-anwr-1002-jpg |

Currently, the status of these protected areas is excellent, and there has been very minimal development and human presence in the area. For instance, the ANWR’s pristine natural condition has been maintained, with an almost non-existent human footprint in the area; there are no roads within or leading into the refuge, except for a few small native settlements.

However, that might not be the case in the future. There has been a long ongoing debate over whether development for oil drilling should be allowed in the ANWR, specifically in the coastal plain “1002 Area”, which was designated as a study area for future congressional decision in “recognition of the area’s potentially enormous oil and gas resources and its importance as wildlife habitat.” A study by the USGS has shown that this area could contain between 5.7 and 16 billion barrels of recoverable oil. Many Republican politicians such as George W. Bush have supported drilling in the ANWR, arguing that this oil is crucial to the American economy and to decreasing the US’s reliance on foreign energy sources. However, drilling in the ANWR would be detrimental to the wildlife and the ecosystem in the area as it would cause mass disturbance and irreversible damage due to the massive infrastructure network that would have to be built, as well as from potential spills which would be detrimental to the surrounding ecosystem.

On the other hand, there is also a large number of politicians who are fighting to keep this refuge protected. Earlier this year, President Obama sent a formal request to Congress to set aside the majority of the ANWR as a wilderness area, an action that would ban oil and gas drilling across 12 million acres. The future of the ANWR is therefore yet to be determined.

Map of the ANWR and NPRA (National Petroleum Reserve, Alaska) area in Alaska

Map of the 1002 Area

Chart on the Volume of Oil in the 1002 Area

In the future, many species will become extinct, Arctic sea ice will decrease significantly, and sea levels will rise unless the world adapts with certain solutions since the average annual temperatures are projected to increase by 4°F to 8°F by the end of the century. A switch to alternative energy would minimize our greenhouse gas emissions since it would minimize the burning of fossil fuels. Fortunately, the US and many other third world countries have begun funding alternative energy research, and their use has slowly started to rise. It’ll also diminish the need for oil and gas, reducing road and pipeline construction. Lastly, the US should establish protected areas to restrict human influence.

Current Status of Alaskan Tundra

A primary ecosystem service of the Alaskan arctic tundra is that it acts as one of the world’s major carbon sinks, a part of the biosphere that holds/absorbs more carbon than it releases. Regular plants, when dying, release carbon into the air; however, in the tundra, plants freeze before they die, trapping the carbon in ice and preventing excess carbon from entering the atmosphere. In addition, another major contribution is that this ecosystem is home to frozen ice! Frozen ice maintains the balance in sea level, and if it were to melt, drastic effects would come into play near coastal areas/islands due to sea level rise.

Future Prospect of the Alaskan Tundra

Currently, human interest in the Alaskan tundra is a result of oil reserves. Were areas in this ecosystem, such as the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, to be converted into oil lands, much disturbance would result from both the drilling and the transport of oil and other materials. Tundra lands are very sensitive to physical disturbances; the construction of roads for oil drilling and the movement of heavy machinery across the land would undoubtedly alter the ecosystem, in particular by precipitating the melting of permafrost (roads tend to hold more heat, and pressure caused by vehicles temporarily lowers the melting point of water).

The Alaskan tundra also faces the threat of global warming, as higher overall temperatures would lead to the loss of permafrost. With permafrost releasing water and nutrients that would otherwise be frozen and locked up, the ecosystem becomes more habitable for coniferous trees. This threatens the tundra as conditions become more favorable for the boreal forest ecosystem to expand into more northern latitudes. Finally, melting permafrost poses a threat to the earth overall, as it currently serves as a carbon sink; melting permafrost would lead to greater decay of organic matter, a process that releases CO2. Without further action to protect the Alaskan tundra, it is likely to shrink in size due to both climate change and direct human interaction; the release of CO2 from melting permafrost would also contribute to an exponential cycle of ecosystem loss, as more CO2 worsens global warming.

Image Gallery

Polar Bear

Polar Bear

Musk Ox

Musk Ox

Pasque Flower

Pasque Flower

Image Gallery

Porcupine Caribou

Arctic Fox

https://www.nwf.org/News-and-Magazines/National-Wildlife/Animals/Archives/2013/Musk-Oxen-Photos.aspx

Rock Ptarmigan

Arctic Willow

Bearberry

Tufted Saxifrage

https://www.google.com/search?q=Tufted+Saxifrage&source=lnms&tbm=isch&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwi369G35qXJAhVBSYgKHSPNCrUQ_AUIBygB&biw=1366&bih=643#imgrc=P9K5IP-saIsQ1M%3A

Bibliography:

Chapin, F. Stuart, III, Sarah F. Trainor, Patricia Cochran, Henry Huntington, Carl Markon, Molly McCammon, A. David McGuire, and Mark Serreze. "Alaska." National Climate Assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, n.d. Web. 22 Nov. 2015.

Defenders of Wildlife. "Arctic National Wildlife Refuge." Defenders of Wildlife. Defenders of Wildlife, 23 Mar. 2012. Web. 25 Nov. 2015.

Hassol, Susan Joy. Impacts of a Warming Arctic: Arctic Climate Impact Assessment. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge UP, 2004. Print.

National Wildlife Refuge Association. "Protecting the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge." National Wildlife Refuge Association. National Wildlife Refuge Association., n.d. Web. 25 Nov. 2015.

S, Whitney. "Alpine Biome." Alpine Biome. Blue Planet Biomes, 2002. Web. 22 Nov. 2015.

"The Tundra Biome." The Tundra Biome. Marietta College, n.d. Web. 22 Nov. 2015.

"Tundra." Alaska Department of Fish and Game. Alaska Department of Fish and Game, n.d. Web. 20 Nov. 2015. <http://www.adfg.alaska.gov/index.cfm?adfg=tundra.main>.

"Tundra." WorldWildlife.org. World Wildlife Fund, n.d. Web. 20 Nov. 2015. <http://www.worldwildlife.org/biomes/tundra>.

"Tundra Threats." National Geographic. National Geographic Partners, LLC., n.d. Web. 22 Nov. 2015.

U.S. Dept. of the Interior, U.S. Geological Survey. The Oil and Gas Resource Potential of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge 1002 Area, Alaska. Denver, CO: U.S. Dept. of the Interior, U.S. Geological Survey, 1999. Http://www.csun.edu/. California State University, Northridge, 1987. Web. 21 Nov. 2015.

Wiesepape, Floyd. "Potential Oil Production from the Coastal Plain of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge: Updated Assessment." Potential Oil Production from the Coastal Plain of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge: Updated Assessment. U.S. Energy Information Administration, 2002. Web. 22 Nov. 2015.

World Wildlife Fund. "Alaska-St. Elias Range Tundra." The Encyclopedia of Earth. The Encyclopedia of Earth, 2014. Web. 22 Nov. 2015.